Neurology

Large doses of antioxidants may be harmful to neuronal stem cells

|

Stem cells are especially sensitive to oxygen radicals and antioxidants shows new research from the group of Anu Wartiovaara in the Molecular Neurology Research Program of University of Helsinki. The research led by researcher Riikka Martikainen was published in Cell Reports -journal May 28th 2015.

Mitochondria are cellular power plants that use oxygen to produce energy. As a by-product they produce reactive oxygen. Excessive oxygen radicals may cause damage to cells but they are needed in small quantities as important cellular signaling molecules. One of their main functions is to control function of stem cells. Antioxidants are widely used to block the damage caused by reactive oxygen. To enhance their effect some new antioxidants are targeted to accumulate into mitochondria.

The current research showed that a small increase in oxygen radicals did not directly lead to cellular damage but disrupted intracellular signaling in stem cells and lead to decrease in their stemness properties. Treatment with antioxidants was able to improve the stemness properties in these cells. However, surprisingly, the researchers found that an antioxidant targeted to mitochondria showed dose-dependent toxic effects especially on neural stem cells.

Repairing the cerebral cortex: It can be done

|

A team led by Afsaneh Gaillard (Inserm Unit 1084, Experimental and Clinical Neurosciences Laboratory, University of Poitiers), in collaboration with the Institute of Interdisciplinary Research in Human and Molecular Biology (IRIBHM) in Brussels, has just taken an important step in the area of cell therapy: repairing the cerebral cortex of the adult mouse using a graft of cortical neurons derived from embryonic stem cells. These results have just been published in Neuron.

The cerebral cortex is one of the most complex structures in our brain. It is composed of about a hundred types of neurons organised into 6 layers and numerous distinct neuroanatomical and functional areas.

Brain injuries, whether caused by trauma or neurodegeneration, lead to cell death accompanied by considerable functional impairment. In order to overcome the limited ability of the neurons of the adult nervous system to regenerate spontaneously, cell replacement strategies employing embryonic tissue transplantation show attractive potential.

A major challenge in repairing the brain is obtaining cortical neurons from the appropriate layer and area in order to restore the damaged cortical pathways in a specific manner.

UTSW researchers identify a therapeutic strategy that may treat a childhood neurological disorder

|

UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have identified a possible therapy to treat neurofibromatosis type 1 or NF1, a childhood neurological disease characterized by learning deficits and autism that is caused by inherited mutations in the gene encoding a protein called neurofibromin.

Researchers initially determined that loss of neurofibromin in mice affects the development of the part of the brain called the cerebellum, which is responsible for balance, speech, memory, and learning.

The research team, led by Dr. Luis F. Parada, Chairman of Developmental Biology, next discovered that the anatomical defects in the cerebellum that arise in their mouse model of NF1 could be reversed by treating the animals with a molecule that counteracts the loss of neurofibromin.

“Children with neurofibromatosis have a high incidence of intellectual deficits and autism, syndromes that have been linked to the cerebellum and cortex,” said Dr. Parada, Director of the Kent Waldrep Foundation Center for Basic Neuroscience Research and holder of the Diana K. and Richard C. Strauss Distinguished Chair in Developmental Biology and the Southwestern Ball Distinguished Chair in Nerve Regeneration Research at UT Southwestern. “Our findings in these mouse models suggest that despite embryonic loss of the gene, therapies after birth may be able to reverse some aspects of the disease.”

To advance care for patients with brain metastases: Reject five myths

|

A blue-ribbon team of national experts on brain cancer says that professional pessimism and out-of-date “myths,” rather than current science, are guiding - and compromising - the care of patients with cancers that spread to the brain.

In a special article published in the July issue of Neurosurgery, the team, led by an NYU Langone Medical Center neurosurgeon, argues that many past, key clinical trials were designed with out-of-date assumptions and the tendency of some physicians to “lump together” brain metastases of diverse kinds of cancer, often results in less than optimal care for individual patients. Furthermore, payers question the best care when it deviates from these misconceptions, the authors conclude.

“It’s time to abandon this unjustifiable nihilism and think carefully about more individualized care,” says lead author of the article, Douglas S. Kondziolka, M.D., MSc, FRCSC, Vice Chair of Clinical Research and Director of the Gamma Knife Program in the Department of Neurosurgery at NYU Langone. The authors - who also say medical insurers help perpetuate the myths by denying coverage that deviates from them - identify five leading misconceptions that often lead to poorer care:

Study Explains How High Blood Pressure in Middle Age Affects Memory in Old Age

|

High blood pressure in middle age plays a critical role in whether blood pressure in old age may affect memory and thinking, according to a study published in the online edition of the journal Neurology.

“Our findings bring new insight into the relationship between a history of high blood pressure, blood pressure in old age, the effects of blood pressure on brain structure, and memory and thinking,” said study author Lenore J. Launer, PhD, National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland.

For the study, 4,057 older participants free of dementia had their blood pressure measured in middle-age (mean age, 50 years). In late life (mean age, 76 years) their blood pressure was re-measured and participants underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans that looked at structure and damage to the small vessels in the brain. They also took tests that measured their memory and thinking ability.

The study found that the association of blood pressure in old age to brain measures depended on a history of blood pressure in middle age. Higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure was associated with increased risk of brain lesions and tiny brain bleeds. This was most noticeable in people without a history of high blood pressure in middle age. For example, people with no history of high blood pressure in middle age who had high diastolic blood pressure in old age were 50% more likely to have severe brain lesions than people with low diastolic blood pressure in old age.

Study reveals workings of working memory

|

Keep this in mind: Scientists say they’ve learned how your brain plucks information out of working memory when you decide to act.

Say you’re a busy mom trying to wrap up a work call now that you’ve arrived home. While you converse on your Bluetooth headset, one kid begs for an unspecified snack, another asks where his homework project has gone, and just then an urgent e-mail from your boss buzzes the phone in your purse. During the call’s last few minutes these urgent requests - snack, homework, boss - wait in your working memory. When you hang up, you’ll pick one and act.

When you do that, according to Brown University psychology researchers whose findings appear in the journal Neuron, you’ll employ brain circuitry that links a specific chunk of the striatum called the caudate and a chunk of the prefrontal cortex centered on the dorsal anterior premotor cortex. Selecting from working memory, it turns out, uses similar circuits to those involved in planning motion.

In lab experiments with 22 adult volunteers, the researchers used magnetic resonance imaging to track brain activity during a carefully designed working memory task. They also measured how quickly the subjects could choose from working memory - a phenomenon the scientists called “output gating.”

Family problems experienced in childhood and adolescence affect brain development

|

The study led by Dr Nicholas Walsh, lecturer in developmental psychology at the University of East Anglia, used brain imaging technology to scan teenagers aged 17-19. It found that those who experienced mild to moderate family difficulties between birth and 11 years of age had developed a smaller cerebellum, an area of the brain associated with skill learning, stress regulation and sensory-motor control. The researchers also suggest that a smaller cerebellum may be a risk indicator of psychiatric disease later in life, as it is consistently found to be smaller in virtually all psychiatric illnesses.

Previous studies have focused on the effects of severe neglect, abuse and maltreatment in childhood on brain development. However the aim of this research was to determine the impact, in currently healthy teenagers, of exposure to more common but relatively chronic forms of ‘family-focused’ problems. These could include significant arguments or tension between parents, physical or emotional abuse, lack of affection or communication between family members, and events which had a practical impact on daily family life and might have resulted in health, housing or school problems.

Dr Walsh, from UEA’s School of Psychology, said: “These findings are important because exposure to adversities in childhood and adolescence is the biggest risk factor for later psychiatric disease. Also, psychiatric illnesses are a huge public health problem and the biggest cause of disability in the world.

Researchers find retrieval practice improves memory in severe traumatic brain injury

|

Kessler Foundation researchers find retrieval practice improves memory in severe traumatic brain injury

Robust results indicate that retrieval practice would improve memory in memory-impaired persons with severe TBI in real-life settings

West Orange, NJ. January 30, 2014. Kessler Foundation researchers have shown that retrieval practice can improve memory in individuals with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). “Retrieval Practice Improves Memory in Survivors of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury,” was published as a brief report in the current issue of Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Volume 95, Issue 2 (390-396) February 2014. The article is authored by James Sumowski, PhD, Julia Coyne, PhD, Amanda Cohen, BA, and John DeLuca, PhD, of Kessler Foundation.

“Despite the small sample size, it was clear that retrieval practice (RP) was superior to other learning strategies in this group of memory-impaired individuals with severe TBI,” explained Dr. Sumowski.

Study finds axon regeneration after Schwann cell graft to injured spinal cord

|

A study carried out at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine for “The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis” has found that transplanting self-donated Schwann cells (SCs, the principal ensheathing cells of the nervous system) that are elongated so as to bridge scar tissue in the injured spinal cord, aids hind limb functional recovery in rats modeled with spinal cord injury.

The study will be published in a future issue of Cell Transplantation but is currently freely available on-line as an unedited early e-pub at: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cog/ct/pre-prints/content-ct1074Williams.

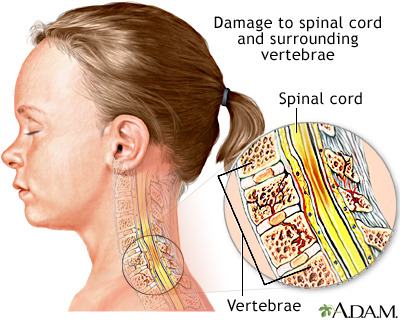

“Injury to the spinal cord results in scar and cavity formation at the lesion site,” explains study corresponding author Dr. Mary Bartlett Bunge of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “Although numerous cell transplantation strategies have been developed to nullify the lesion environment, scar tissue - in basil lamina sheets - wall off the lesion to prevent further injury and, also, at the interface, scar tissue impedes axon regeneration into and out of the grafts, limiting functional recovery.”

The researchers determined that the properties of a spinal cord/Schwann cell bridge interface enable regenerated and elongated brainstem axons to cross the bridge and potentially lead to an improvement in hind limb movement of rats with spinal cord injury.

Recurring memory traces boost long-lasting memories

|

Bonn, Germany, December 5th, 2013 - While the human brain is in a resting state, patterns of neuronal activity which are associated to specific memories may spontaneously reappear. Such recurrences contribute to memory consolidation - i.e. to the stabilization of memory contents. Scientists of the DZNE and the University of Bonn are reporting these findings in the current issue of The Journal of Neuroscience. The researchers headed by Nikolai Axmacher performed a memory test on a series of persons while monitoring their brain activity by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The experimental setup comprised several resting states including a nap inside a neuroimaging scanner. The study indicates that resting periods can generally promote memory performance.

Depending on one’s mood and activity different regions are active in the human brain. Perceptions and thoughts also influence this condition and this results in a pattern of neuronal activity which is linked to the experienced situation. When it is recalled, similar patterns, which are slumbering in the brain, are reactivated. How this happens, is still largely unknown.

The prevalent theory of memory formation assumes that memories are stored in a gradual manner. At first, the brain stores new information only temporarily. For memories to remain in the long term, a further step is required. „We call it consolidation“, Dr. Nikolai Axmacher explains, who is a researcher at the Department of Epileptology of the University of Bonn and at the Bonn site of the DZNE. “We do not know exactly how this happens. However, studies suggest that a process we call reactivation is of importance. When this occurs, the brain replays activity patterns associated with a particular memory. In principle, this is a familiar concept. It is a fact that things that are actively repeated and practiced are better memorized. However, we assume that a reactivation of memory contents may also happen spontaneously without there being an external trigger.”

TB Vaccine May Work Against Multiple Sclerosis

|

A vaccine normally used to thwart the respiratory illness tuberculosis also might help prevent the development of multiple sclerosis, a disease of the central nervous system, a new study suggests.

In people who had a first episode of symptoms that indicated they might develop multiple sclerosis (MS), an injection of the tuberculosis vaccine lowered the odds of developing MS, Italian researchers report.

“It is possible that a safe, handy and cheap approach will be available immediately following the first [episode of symptoms suggesting MS],” said study lead author Dr. Giovanni Ristori, of the Center for Experimental Neurological Therapies at Sant’Andrea Hospital in Rome.

But, the study authors cautioned that much more research is needed before the tuberculosis vaccine could possibly be used against multiple sclerosis.

Discovery of gatekeeper nerve cells explains the effect of nicotine on learning and memory

|

|

Swedish researchers at Uppsala University have, together with Brazilian collaborators, discovered a new group of nerve cells that regulate processes of learning and memory. These cells act as gatekeepers and carry a receptor for nicotine, which can explain our ability to remember and sort information.

The discovery of the gatekeeper cells, which are part of a memory network together with several other nerve cells in the hippocampus, reveal new fundamental knowledge about learning and memory. The study is published today in Nature Neuroscience.

The hippocampus is an area of the brain that is important for consolidation of information into memories and helps us to learn new things. The newly discovered gatekeeper nerve cells, also called OLM-alpha2 cells, provide an explanation to how the flow of information is controlled in the hippocampus.

“It is known that nicotine improves cognitive processes including learning and memory, but this is the first time that an identified nerve cell population is linked to the effects of nicotine”, says Professor Klas Kullander at Scilifelab and Uppsala University.

Increasing care needs for children with neurological impairment

|

|

In this week’s PLoS Medicine, Jay Berry of Harvard Medical School, USA and colleagues report findings from an analysis of hospitalization data in the United States, examining the proportion of inpatient resources attributable to care for children with neurological impairment (NI). Their results indicate that children with NI account for a substantial proportion of inpatient resources and that the impact of these children is growing within children’s hospitals, necessitating adequate clinical care and a coordination of efforts to ensure that the needs of children with NI are met.

The authors state: “We must ensure that the current health care system is staffed, educated, and equipped to serve, with efficiency and quality, this growing segment of vulnerable children.”

###

Funding: AP was supported by the Harvard Medical School Eleanor & Miles Shore Scholar/Children’s Hospital Boston Junior Faculty Career Development Fellowship. RS and JGB were supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development career development awards K23 HD052553 and K23 HD58092-02, respectively. JLB was supported by NIH K08 DA024753. This project was supported in part by the Children’s Health Research Center at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Medical Center Foundation. The funders and sponsors were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Neurologically impaired children dependent on children’s hospitals

|

|

Because of care advances, more infants and children with previously lethal health problems are surviving. Many, however, are left with lifelong neurologic impairment. A Children’s Hospital Boston study of more than 25 million pediatric hospitalizations in the U.S. now shows that neurologically impaired children, though still a relatively small part of the overall population, account for increasing hospital resources, particularly within children’s hospitals. Their analysis, based on data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID), was published online January 17th in PLoS Medicine.

The researchers analyzed KID data from 1997, 2000, 2003 and 2006, encompassing 25.7 million hospitalizations of children age 0 to 18. Of these, 1.3 million hospitalizations were for children with neurologic conditions, primarily cerebral palsy and epilepsy.

During the 10-year period, children with neurologic diagnoses were admitted more to children’s hospitals and less to community hospitals. At non-children’s hospitals, they made up a falling share of admissions (from 3 percent in 1997 to 2.5 percent in 2006); at children’s hospitals, they made up a rising share (from 11.7 percent of admissions in 1997 to 13.5 percent in 2006).

What you want versus how you get it

|

|

New research reveals how we make decisions. Birds choosing between berry bushes and investors trading stocks are faced with the same fundamental challenge - making optimal choices in an environment featuring varying costs and benefits. A neuroeconomics study from the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital – The Neuro, McGill University, shows that the brain employs two separate regions and two distinct processes in valuing ‘stimuli’ i.e. ‘goods’ (for example, berry bushes), as opposed to valuing the ‘actions,’ needed to obtain the desired option (for example flight paths to the berry bushes). The findings, published in the most recent issue of the Journal of Neuroscience and funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, are vital not only for improving knowledge of brain function, but also for treating and understanding the effects of frontal lobe damage, which can be a feature of common neurological conditions ranging from stroke to traumatic brain injury to dementia.

Decision making - selecting the most valuable option, typically by taking an action - requires value comparisons, but there has been debate about how these comparisons occur in the brain: is value linked to the object itself , or to the action required to get that object. Are choices made between the things we want, or between the actions we take? The dominant model of decision making proposes that value comparisons occur in series, with stimulus value information feeding into actions (the body’s motor system). “So, in this study we wanted to understand how the brain uses value information to make decisions between different actions, and between different objects,” said the study’s lead investigator Dr. Lesley Fellows, neurologist and researcher at The Neuro. “The surprising and novel finding is that in fact these two mechanisms of choice are independent of one another. There are distinct processes in the brain by which value information guides decisions, depending on whether the choice is between objects or between actions.” Dr. Fellows often sees patients with damage to the frontal lobe, where decision making areas of the brain are located. “This finding gives me more insight into what is happening in the brain of my patients, and may lead to new treatments and new ways to care for them and manage their symptoms.”

“Despite the ubiquity and importance of decision making, we have had, until now, a limited understanding of its basis in the brain,” said Fellows. “Psychologists, economists, and ecologists have studied decision making for decades, but it has only recently become a focus for neuroscientists.